13 Oct 2022

Oftentimes when I’m experimenting in a project I make a bunch of changes and then want to keep some of them (without committing) but undo the rest. I would try to stage the changes that I didn’t want and them stash them like this:

git add path/to/undesired/changes

git stash

But this would stash everything, including the changes I wanted to keep.

I tried being more specific with stash bu providing a path, but no dice.

$ git stash path/to/undesired/changes

fatal: unknown subcommand: path/to/undesired/changes

I think in an older version of Git this used to work, but I found the updated command today: git stash push _path_ --keep-index

$ git stash push path/to/undesired/changes --keep-index

Saved working directory and index state WIP on _branch_name_: 32dbc82 .

Thanks to this post.

05 Oct 2022

I rarely define methods that use them so I often forget. There are a few different ways to define keyword arguments in a method.

A method can be defined with positional arguments, keyword arguments (which are defined and called using the : syntax) or have no arguments at all.

class Calculator

# Positional arguments

def add(num1, num2)

return num1 + num2 # Explicit return

end

# Keyword arguments

def multiply(num1:, num2:)

num1 * num2 # Implicit return

end

end

You can also now pass the arguments in whatever order with keyword arguments.

c = Calculator.new

c.multiply(num2: 3, num1: 9)

# => 27

Which brings us to first way to define keyword arguments, by adding the : to the end.

Approach #1

def hello(message:)

puts "hello " + message

end

hello # => ArgumentError: missing keyword: message

hello(message: 'world') # => 'hello world'

You can also define default values for these keywords like this:

def hello(message: "everyone")

puts "hello " + message

end

hello # => 'hello everyone'

hello(message: 'world') # => 'hello everyone'

Just having the : at the end with no default value always looked incorrect to me (which is probably why I forget about it), since it feels pretty rare for Ruby to determine the “type” of something by the ending character instead of the starting character, but it’s probably a hold over from C or something.

Approach #2

def grab_bag(**keyword_arguments)

p keyword_arguments

end

grab_bag(letter: "m", some_number: 31)

# => {:letter=>"m", :some_number=>31}

If you want to accept keyword arguments, in principle you should always use def foo(k: default) or def foo(k:) or def foo(**kwargs)

Ruby 3 Changes

In Ruby 3.0, you must explicitly specify which arguments are keywords (using the double splat) instead of relying on Ruby’s implicit last-argument-is-a-hash thing.

In Ruby 2, keyword arguments can be treated as the last positional Hash argument and a last positional Hash argument can be treated as keyword arguments.

Basically, in situations like this

def one_keyword(keyword: 1)

p keyword

end

hash = { keyword: 42 }

and you want to pass hash as an argument to one_keyword, you can’t do this anymore:

one_keyword(hash)

# => wrong number of arguments (given 1, expected 0) (ArgumentError)

In Ruby 3+ this will throw an Argument error. Now, the syntax is to pass the argument with the double splat like this:

one_keyword(**hash)

=> 42

The other situation when you have a method with both types of arguments:

def mixed_arguments(positional, **keywords)

p positional

end

If positional is supposed to be a Hash, you have to explicitly declare it as such.

This won’t work:

mixed_arguments(word: 42)

This will work:

mixed_arguments({word: 42})

More reading

01 Sep 2022

Sometimes when you are debugging a Ruby script, you want to do more than just print variables to debug. It’d be nice to pause the program at a particular moment and actually interact with all the variables that have been defined up until that point. Turns out, you can do this by adding breakpoints to your script.

a breakpoint is an intentional stopping or pausing place in a program, put in place for debugging purposes.

— Wikipedia

Breakpoints can be added to your Ruby script using the pry library, which is a part of the standard Ruby library, but isn’t automatically loaded. You can load the library with require "pry".

Pry basics

Let’s say we have a program like this:

list_of_people = [

{ :name => "James", :age => 16 },

{ :name => "Yolanda", :age => 26 },

{ :name => "Mel", :age => 15 }

]

p "Enter an age and we'll tell you if we know a person who is that old:"

age_to_find = gets.chomp

list_of_people.each do |person|

if person.fetch(:age) == age_to_find

p "Found it!"

end

end

Even when I enter an age that I know should be found, like 16, my program doesn’t print "Found it!" like I expect.

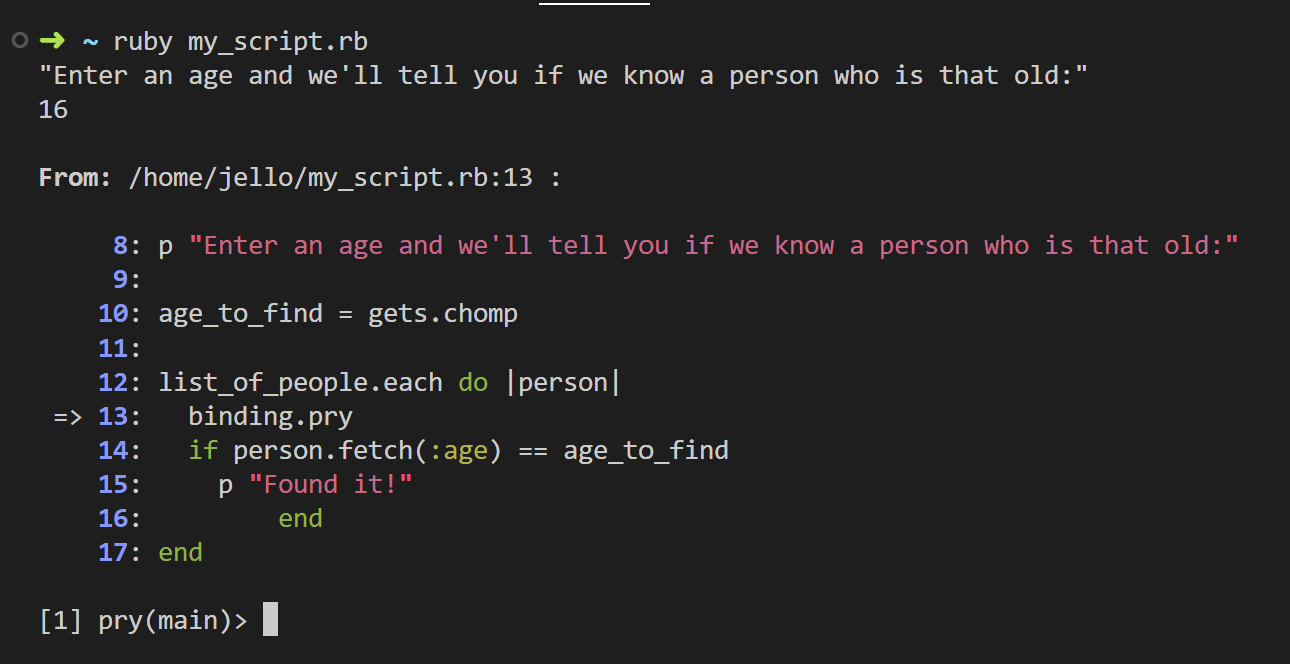

Using pry, I can use binding.pry to add a breakpoint before the if statement so I can interact more with the variables that were created.

binding.pry will pause the runtime of the program and open an IRB console

list_of_people = [

{ :name => "James", :age => 16 },

{ :name => "Yolanda", :age => 26 },

{ :name => "Mel", :age => 15 }

]

p "Enter an age and we'll tell you if we know a person who is that old:"

age_to_find = gets.chomp

list_of_people.each do |person|

binding.pry

if person.fetch(:age) == age_to_find

p "Found it!"

end

end

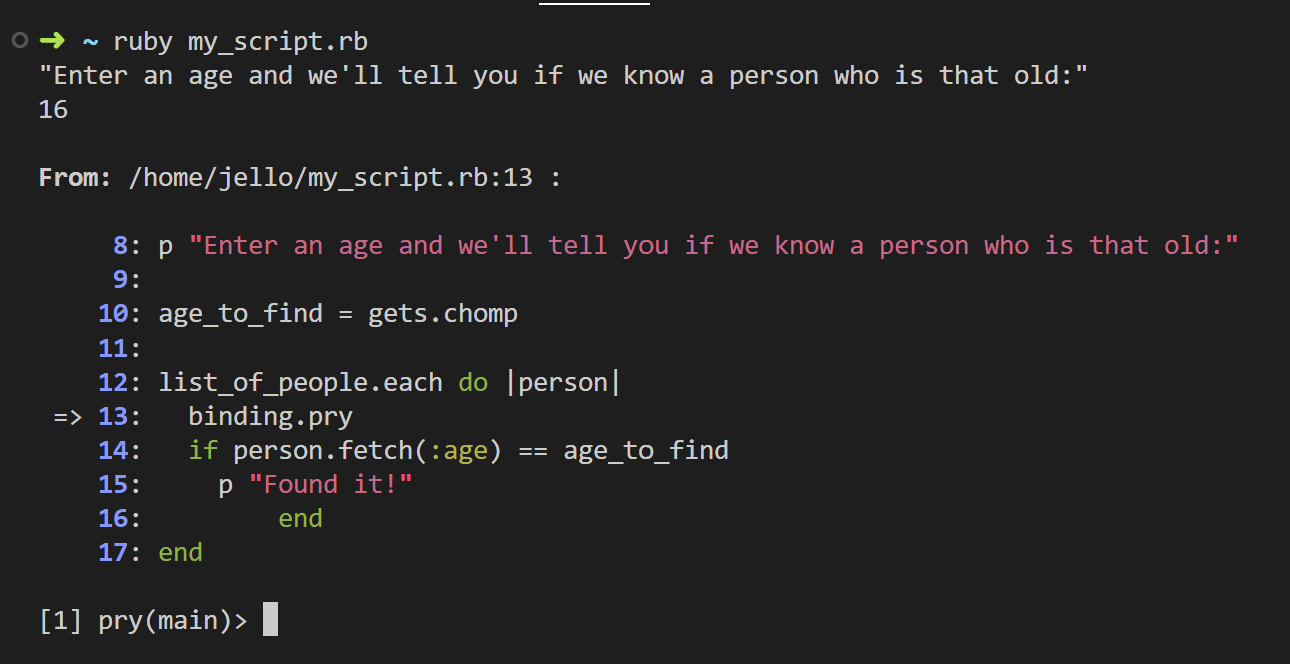

Now when you run the program it doesn’t complete—

You can use an IRB console to interact with the code that has run so far.

Now I can access variables like age_to_find and person that were defined before the breakpoint to see why the condition for my if statement never evaluates to true.

Ah, the ol’ forget-to-convert-a-String-into-an-Integer error. Gets me everytime 🤦. Now I know to convert age_to_find to an Integer.

You can type exit when you’re done to un-pause the programs execution.

02 May 2022

I recently was looking into how to use Ruby with AWS Lambda for *reasons*, and it took a lot of time! I finally figured out how to do it and even test locally with containers.

I already wrote a bunch of stuff up in this repository, which the README will be updated with any nice resources I find as I continue learning.

19 Apr 2022

TIL, OAuth and SAML are not the same and do slightly different things. You would never use them both at the same time.

OAuth

OAuth is for authorization. The best example I have is when I used my Google account for Pokémon Go. After logging in with my Google account, the Pokemon Go app prompted me to ask if they could have permission to access a bunch of things in my Google account. I didn’t follow it, but there was a bunch of news about how Pokémon Go requested you grant too much access to the Google account. Anywho, OAuth is the protocol used to authorize other services to have access to things in your Google account. Facebook does the same. You may even see apps that say, “Login with your Facebook or Google account and we’ll import all your contacts into our system.” That’s OAuth being used by Facebook and a Google to authorize other services to access resources in your account.

SAML

SAML is a protocol for authentication. Basically, you have a service provider (Salesforce, G Suite, Box, etc) and you have an identity provider (Okta, OneLogin, Ping Identity, etc). You’ll have a user account in both systems, let’s say for Jane. When Jane goes to login to Box, she would typically provide a username and password, then Box would authenticate the user. But the IT admins have setup SAML with Box and Okta. So when Jane goes to Box to login now, Box sends a SAML request to Okta. Okta receives that request and may ask the user to login to Okta, if they haven’t already. Okta is essentially tasked with authentication. Okta then sends a SAML response to Box. Box accepts this and creates a session for the user and they’re now logged in. To Box, the SAML response they received is used instead of them providing a username and password.